Vaccinations and the Human Race as Bread Mold

Things that come up in this post:

- travel vaccinations for Japanese encephalitis, rabies, and polio at the NTU travel clinic

- cycling around the world

- the life cycle of the human race is like the growth of bread mold

- woodblock prints exhibit at the National Museum of History in Taipei

- Changsha porcelain exhibit at the National Museum of History in Taipei

- the eight deities in ivory, oracle bones, and silver ingots that look like gravy boats

- modifying an Arkel pannier bag so that it can be used as a knapsack when off the bike

Wednesday Janaury 30, 2013

Outdoor Coffee Shop on Zhongshan Rd. Taipei

Preparations continue for my departure from Taiwan and flight to the Philippines. I just came from NTU hospital, where I received my final shots for rabies and Japanese encephalitis. I have to return one more time for a final polio shot. I’m a bit confused about the polio vaccines I’ve been getting. It seems like I was already vaccinated against polio for life. But apparently not.

I have the system at the Travel Clinic pretty much wired at this point. I was patient number two at the clinic and was seen shortly after 9 a.m., as patient number one didn’t show up. Unfortunately, my usual doctor was not there. There was a new doctor and she didn’t instill much confidence. Luckily, there wasn’t much for her to do. She simply had to look up my records and then ask me if I had had any kind of adverse reaction to the previous vaccinations. As on many other occasions at hospitals, it was the nurse who was essential to this operation and really knew what was going on. She knew what I was there for and how to call up my records and what forms to fill out and all of that. The doctor was being led by the hand by the nurse. I wrote earlier after previous visits that I was quite impressed by the professionalism of the travel clinic, but I also have a vague sense of unease. The doctor often seems to rely too much on what I tell her, as if she has no idea what is going on and needs me to tell her. And what if, as the patient, I don’t know or I make a mistake?

The consultation with the doctor was short and sweet and then I went down to the cashier in the lobby to pay. Vaccinations are not covered by health insurance, so I had to fork over the princely sum of NT$3,122, or about $100 US. That is the final large amount I’ll have to pay. Now I definitely have to travel for a long time and see everything there is in the world to see in order to make all this effort and expense worthwhile. When I started thinking about this trip. I was thinking in terms of staying on a strict budget. I’m not sure when that budget is going to kick in because so far it has been an expensive proposition, and I haven’t gone anywhere! I had money set aside for vaccinations but not $500 US. I had had no idea it would be that expensive.

Once I paid, I then popped over to the pharmacy to pick up my three vaccines. Again, I was quite surprised at how quickly my vaccines were ready. Just a few minutes had passed since my consultation with the doctor, but everything was sitting there right at the window and waiting for me. The clerk asked me for my name and birth date and compared that with the info on the package. Once I had my vaccines, I went back up to the travel clinic to the treatment room. The same nurse has been there each time, and we greet each other like old friends now. The last time I was there, I made a strong effort to stay on top of the proceedings – to be proactive. The nurse remembered that, and she showed me everything she was doing and let me examine the packaging for each vaccine and made sure I understood which one I was getting each time. I followed her instructions to take a “deep breath” for each injection and it was done in a short time. We joked and laughed about how many vaccines I had gotten and that I would have to return one more time. She applauded at the idea that I was almost done. She is very nice.

There wasn’t as much chaos in the hospital as on my previous visit. It wasn’t as busy, so I wasn’t pushed around and bumped into and run into by wheelchairs quite as much. Still, I had to be on my toes. Being a hospital, there were quite a few elderly people milling around and they don’t care that much about getting in peoples’ way. They also move at very slow speeds and follow erratic paths across rooms, so moving past them and around them took some care and patience.

I don’t think I’m someone that dwells on age and the passage of time that much. I find the constant references to getting older from other people more boring than anything else. The passage of time and the breaking down of our bodies is about as interesting as the weather as a topic of conversation, and I make a mental effort to avoid it. It’s like a conversational habit that you can get into and then it’s hard to get out of it. Having said that, when you spend time in hospitals, you can’t help but devote a few brain cells to pondering the inevitably of old age and death. As I said, I’m not hung up on death in any way. It’s all good. And in terms of what is out there in the world, I’ve already won the lottery in terms of good health and number of years. I have no complaints and have no dread of what is to come. But when I see these elderly people in the hospital being pushed around on wheelchairs and others barely being able to make it up two steps, I have a quickening of appreciation for my good, strong legs and become quite glad that I’m about to embark on the classic trip around the world. As far as I know, my legs and body will have no more than the usual amount of trouble propelling me around the planet on a bicycle, and I don’t know if that will still be true in say ten or fifteen years. And however many delusions one might have deep in one’s brain about being the exception to the rule – about being the one human that doesn’t get old and die – it’s easy to see the reality in a hospital. At some point, I will be unable to walk up stairs. Strange to think of that, but that’s the way it is.

While wandering around the hospital, lost in my thoughts, I had another glimpse of the human race as a species and not as individuals. There was so much activity going on around me, so many people doing things to themselves and to other people to keep their bodies going and functioning just that little bit longer. Yet, all of that activity doesn’t really serve any purpose other than to keep the species alive – to produce more of us so that they can then produce more of us and then more of us and keep it up as long as possible till the species dies out. I often like to imagine the human race to be like mold on a piece of bread that has been left out – it grows and spreads and reaches a maximum size and then uses up all the energy in the bread and then dies – the rise and fall of a mold civilization in the matter of a few days. It’s not a hard mental leap (especially for someone with a steady diet of science and science fiction) to see the human race in the same way. You just have to adjust your time scale. And that isn’t hard at all when you start to put things in perspective and put the history of the human species next to the life of the planet or the solar system or the galaxy or whatever you want. From any one of those perspectives, the rise and fall of the human species will be exactly like the sudden growth and death of that mold on a slice of bread – over in a blink of the eye. Anyway, those were my thoughts as I sat there on my chair and watched all these people around me.

The other big bit of departure preparations occurred on the weekend. This was the relatively minor (but very important to me) task of attaching shoulder straps to one of my pannier bags. Pannier bags are very important to a long-distance cyclist. I have a set of four Arkel pannier bags, which I purchased many, many years ago. They are heavy-duty bags with lots of pockets and fancy features. I love them. A problem with pannier bags, though, is that they are designed to attach to a rack on a bicycle and are a bit awkward to carry around in any other way. Arkel responded to that by designing some pannier bags that convert to knapsacks. They have shoulder straps that tuck away when you don’t need them. That would be ideal except that they did this to their front pannier bags and to a special commuter urban bag. The front pannier bags are too small for my purposes to be used as a knapsack, and the urban bag (the “Bug”) does not have a design suitable for me. I’ve been thinking about adding shoulder straps of my own, and I finally got around to doing that this weekend. It took a long time to do, but as it turned out it was fairly simple.

I made the modifications to one of my big rear pannier bags. This bag already has a couple of big plastic rings mounted on the top. All I really needed to do was put attachment points on the bottom of the bag and then I’d be able to hook on shoulder straps. They couldn’t be permanent, of course. I’d have to remove them each time I wanted to put the pannier bag on the bike, but that’s okay.

I won’t go through the long process I went through to come up with my final design. I had to do a lot of experimenting and testing, but in the end, all I did was drill two holes at the bottom on the back of the bag and insert two bolts with a large washer on each. I had drilled a hole through the edge of each washer and bent up the edge in a vise. Then I put a loop of heavy duty cord through the hole in the washer. Voila. Done. Now to convert my pannier bag to a knapsack, all I have to do is attach two shoulder straps – the top end to the plastic ring and the bottom to the washers. I already have a couple of straps that are perfect for this, and I am almost done. All I have to do now is cut those straps to the proper length and then sew them up. It’s not perfect. Nothing could be. Pannier bags first and foremost are designed to mount on a bicycle. To that end, they are rugged and square and have all kinds of hard edges and sharp metal bits. Taking something like that and suddenly putting it on your back as a knapsack is not that comfortable. Yet, I found when I had finished all of my work that it wasn’t that bad. The big hook in the middle of the bag fits more or less in the small of my back and doesn’t dig into me. The big hooks on the top end up are placed away from my shoulders and don’t dig into me either. So it’s a pretty good design. I’ll probably take a couple of pictures and send them to Arkel. My work is crude in the extreme, but it might interest them to see what I’ve done. I wrote to them a long time ago to give them my thoughts on their Bug pannier bag and the front pannier bags that convert into knapsacks. I told them in my email that I would prefer a rear pannier bag to be convertible into a knapsack. I think I might be unique in that. Yet, maybe not. Most people who are traveling with a knapsack would want to keep a certain number of things with them – a camera, maps, guidebook, jacket, water, snacks, netbook, etc. For me, that amount of stuff doesn’t fit into a front pannier bag. I have to use a rear pannier bag as my main bag for that.

1:26 p.m.

After my trip to the hospital, I stopped for a cup of coffee and then I walked down Zhongshan Road to Nanhai Road. At the intersection, there is a small market, and I picked up a few snacks. I munched on those as I walked the final two or three blocks to the National Museum of History. The big new exhibit there is on Michelangelo. Once I got there, I decided to give that a miss. These traveling exhibits can be a bit lightweight, and I got the impression that there wasn’t much to interest me in this exhibit. Some of the ones based on famous artists seem to focus more on the gift shop at the end than anything else. They are more like elaborate gimmicks to get people into the gift shop than a serious presentation of an artist and their work. There were a number of other new exhibits at the museum, and I was more interested in those. Besides, the Michelangelo exhibit cost $250 and a ticket to the main museum is only NT$30.

The first exhibit I took in was called “Changsha Porcelain from NMH Collection.” This porcelain was from the Tang dynasty and dated from around 800-900 A.D. There were fifty or sixty pieces on display – all beautiful pieces. According to the volunteers at the museum, the ceramics from the Changsha kiln were among the earliest “trade porcelain of China.” I’m not entirely sure what that means, but I gather that this porcelain was carried along the silk road and sold in the Middle East and Europe. The design of these pots struck me as unusual. They didn’t seem Chinese to me. Most of the pieces were water pots and they each had a spout for the water. The spouts were not rounded but had sharp edges all around. I don’t know how to describe it. They had a geometric shape, like an octagon rather than being round. That, plus the overall shape of the pots, struck me as classical Greek or Roman rather than Chinese. Of course, I have no idea what I’m talking about, but that’s how they seemed to me.

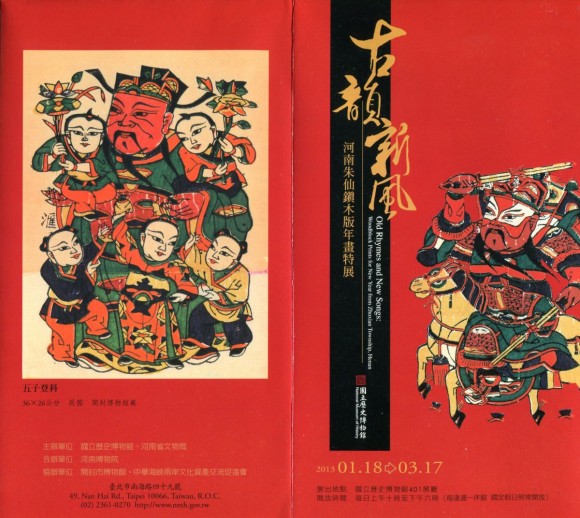

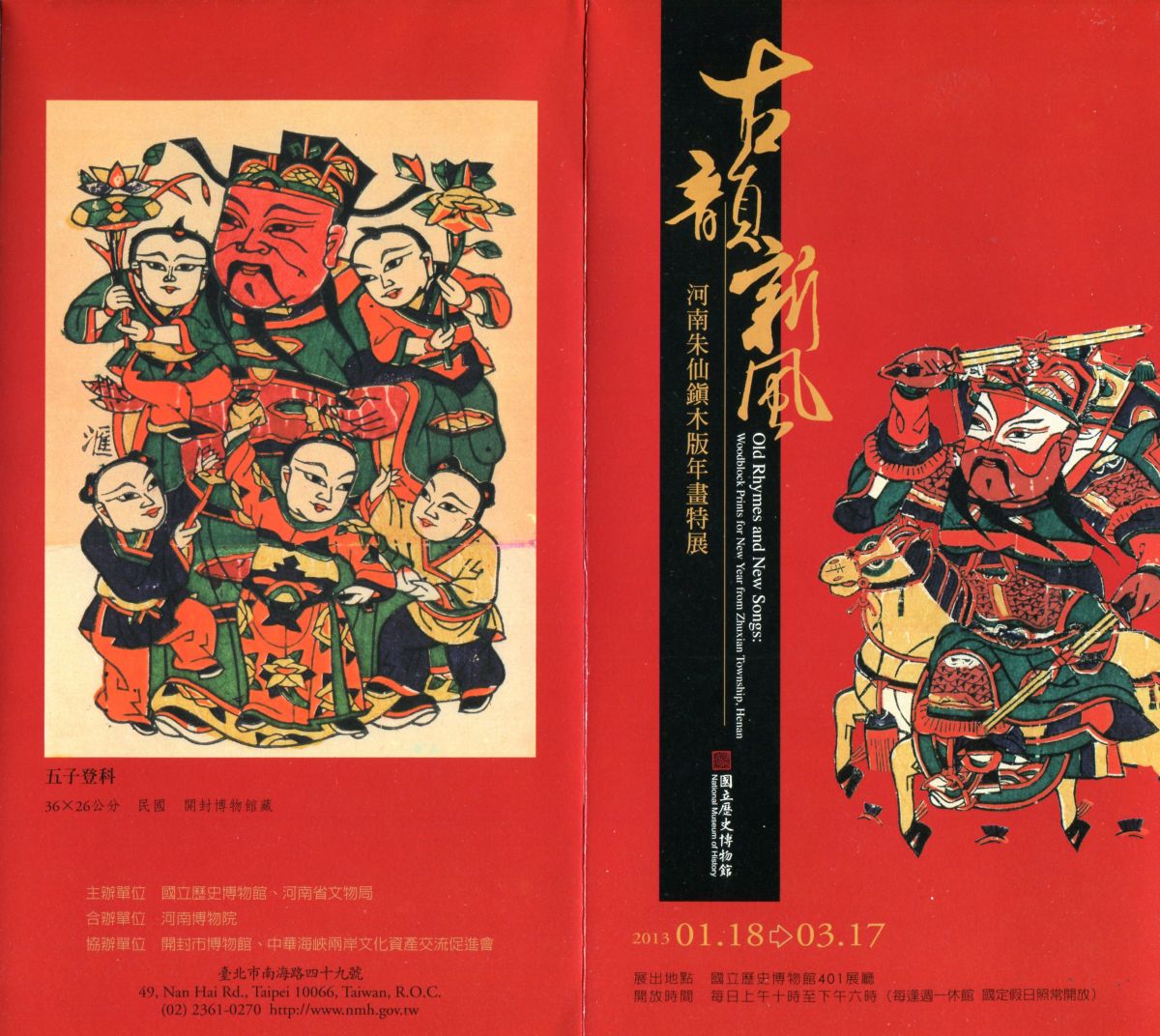

Another interesting exhibit was of New Year woodblock prints called “Old Rhymes and New Songs.” These woodblock prints came from Zhuxian township in Kaifeng, Henan in China. Fifty-two prints are on display along with some exhibits showing the process and tools for making them. I don’t know why they are referred to as New Year prints. The scenes on them are taken from historical dramas, novels, myths and folk tales. They are simple drawings, somewhat stylized with four or five bright primary colors. I was very interested to watch a video showing the exact steps used to make them. An older man used traditional tools – bamboo and stones and brushes made from reeds and other plants. It was fascinating to watch him at work. It cleared up a lot of questions I had about making prints. I had the basic idea, but I wasn’t clear about how they managed to apply so many different colors. The trick, of course, is that there is a separate woodblock for each color and each woodblock is carved separately to mark different parts of the final picture. The key technique is that the blocks and then the papers have to be lined up with extreme precision for the final picture to come together. The printer made a couple of hundred of prints at a time with the thick bundle of paper lined up carefully and then held together tightly by a piece of split bamboo. Like most art and craftwork, it looked easy as the man was doing it, but I can imagine that it took extreme skill and practice to get it right – particularly to do it at the speed that he was working. And that is just the making of the prints themselves. Carving the many different woodblocks would be the real challenge, particularly since they have to be reversed in order to produce the proper image. I’ll have to ask around and find out why woodblock prints are associated with the New Year.

There is always something new in the main exhibit of Huaxia artifacts, and I went through there as well. I have a few favorite pieces on that floor including a matching set of the eight deities carved out of ivory. They’re very beautiful and elegant. They also have some samples of oracle bones there. I find the oracle bones fascinating. There is also a display of silver ingots and other forms of money. These puzzle me because they are so crude and unshapely. Chinese art seems to have developed very early and it is very precise and elaborate in all its forms. Yet, the money looks like it was slapped together by someone with only the most rudimentary tools. You’d think that something as important as your empire’s currency would have the highest level of artistry. Yet, these silver ingots are just big chunks of metal somewhat in the shape of a gravy boat. I guess they are shaped that way partially so that they can be stacked, but they are very crudely made and don’t seem to match either.

The amount of art produced in China over the centuries always astonishes me no matter where I see it or how I encounter it. As I walk through these museums, I always end up thinking about the artisan class that made them. I think it’s a standard idea that any particular civilization has to reach a certain level of prosperity to begin producing art. In essence, there has to be enough food and other goods produced by farmers and workers so that there is a surplus and other people are free to do other things – became artisans essentially. If everyone is farming to survive, no one would have the time to develop art and science and literature and everything else. I can’t claim to understand artists, however. If everyone in the world were like me, there would be no art. I go for function over form. I would build something that was useful, but I don’t think I have the artistic urge anywhere inside me. I might see the need for a water pot and I might put some effort into discovering clay and pottery. However, once done, I would be quite happy with my unadorned water pot. I doubt I would then feel the need to paint birds on it.

Tags: Arkel pannier bags, China, National Museum, New Year, NTU, Taipei